The descendants of Manchu bannermen believe that the Manchus of northeastern China and the Koreans share a common ancestral homeland: a single mountain, called Golmin Šanggiyan Alin in the Manchu language, Chángbáishān in Chinese, and Paektusan in Korean. In my family, we’ve always regarded Koreans as some kind of kin. They were distant relatives whose doors we never knocked on to borrow sugar, pay a New Year’s visit, or exchange recipes for kimchi.

Still, I felt our kinship. At the entrance to Gyeongbokgung, Korea’s primary palace during its 500-year Joseon dynasty, it stared me squarely in the eyes. I recognized the three Chinese characters on the plate of the main gate instantly. 光化門—Guānghuàmén, when the plaque is read traditionally, from right to left. Gwanghwamun, when pronounced in Korean. The meaning they convey is the same in both languages. The first character stands for “light,” the second for “transformation,” and the final one for “gate.” Altogether: Gwanghwamun, the gate of transformative light, or enlightenment.

All of Gyeongbokgung’s gates bear name plates in hanja, classic Chinese characters adapted for the Korean language. Prior to the introduction of the native Korean alphabet (known in South Korea as hangul) by the Joseon-era king Sejong in 1443, Korean was written exclusively in hanja. Lexically, the language was also influenced by Chinese. It is estimated that anywhere from one-third to two-thirds of all Korean vocabulary are words of Chinese origin; these are referred to as Sino-Korean words.

The invention of hangul led to the emergence of a new form of writing, a mixed script which combined Chinese ideograms with native Korean letters. Sino-Korean words were transcribed in hanja, and native Korean ones were spelled out in hangul. Korean mixed script gradually replaced documents written exclusively in hanja in the 20th century, although it too lost favor later in the 21st century, ceding to hangul-only writing. At the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, I followed the decline of hanja and Korean mixed script with fascination through the vitrines of decrees and documents.

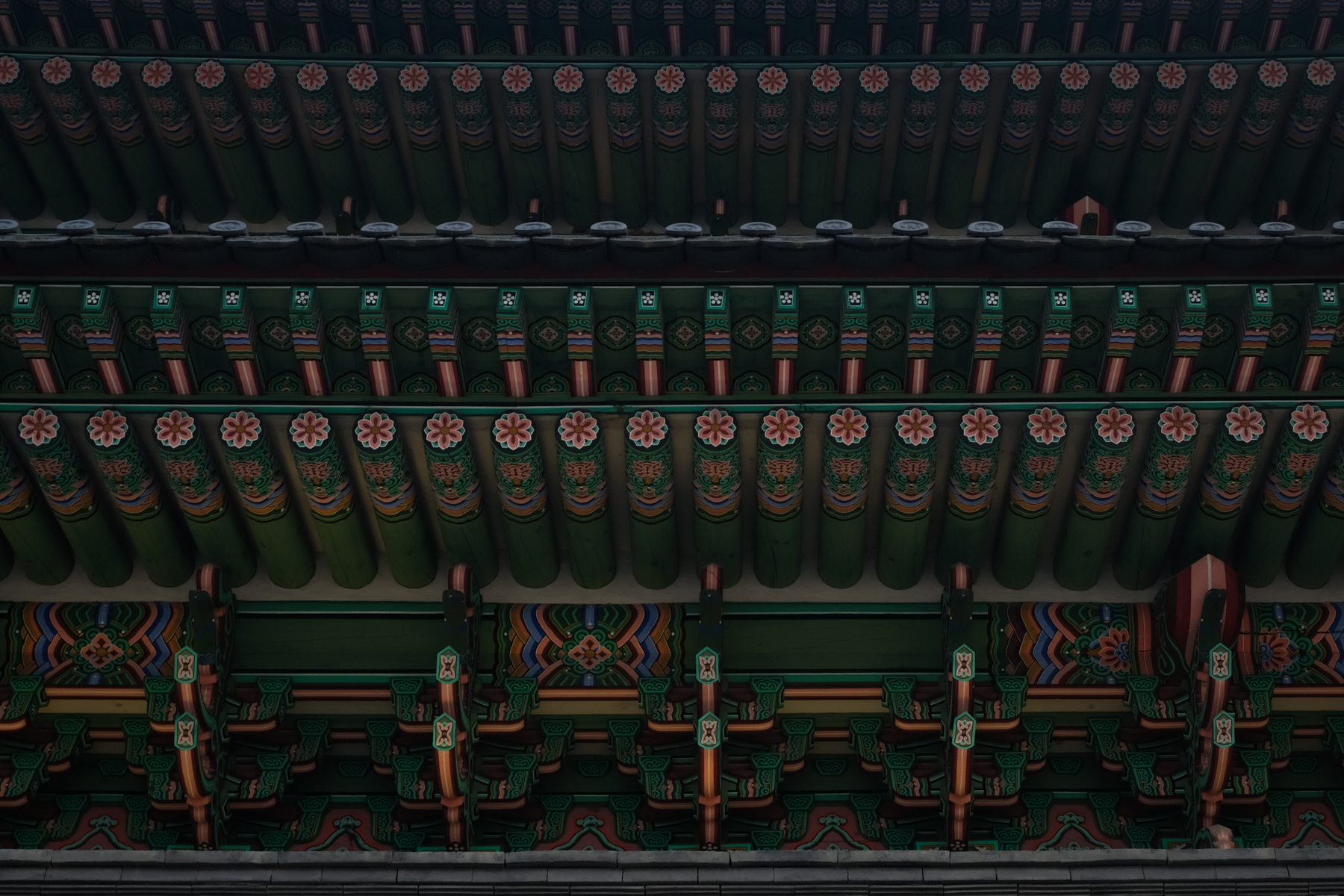

I felt our kinship in the architecture too. At Gyeongbokgung and the Buddhist center of Jogyesa, the vibrantly painted beams conjure up the calming and luxurious qualities of the most precious jades. They are the finest examples of dancheong (단청; 丹靑), one of Korea’s intangible cultural heritages. Both Buddhism and dancheong traveled from China to Korea, where, over the centuries, they took on distinct peninsular features. The prominent usage of green in dancheong decorations, for example, arose during the Joseon period.

Elsewhere in Seoul, traditional residential neighborhoods known as hanok (한옥; 韓屋) villages call to mind the narrow alleyways of Beijing. But they are tidier, shinier. The black eaves, or cheoma (처마; 檐下), curve gracefully up towards the sky. Beyond aesthetics, their unique shape serves a practical purpose. During the cold winter months, they invite sunlight into the houses below them. And during the typhoon season, the cheoma protect the wood from the furious and angled rain.

I felt our kinship in the jjimjilbang (찜질방; 蒸氣房), the elaborate South Korean bathhouse. The various themed kiln saunas of clay, salt, crystals, and even ice were exotic and exciting, but the bathing area—known as the mokyoktang (목욕탕; 沐浴湯)—could have been lifted right from my memories. They were the same as the bathhouses I frequented with my grandfather during my adolescent summers in China. How wonderful it was to find the same plastic stools, steam rooms, and hot pools again in Korea. How I missed the rough and thorough scrubs and rhythmic back pats of a professional bath master.

I felt the kinship not only in tradition, but in development too. I saw fragments of America in Seoul, and the legacy of the servicemen and missionaries posted on this side of the 38th parallel. I found comfort in the coffee chains and the endless cups of unsweetened iced Americanos they churned out, and in the Southern-like crunch of Korean fried chicken, whose origins some attribute to African-American GIs. Even the prolific number of Christian churches that blanket the city seemed to smile, flashing their pearly lights and lofty crosses like the young, mild-mannered missionaries we invited into our homes in California.

고래 싸움에 새우 등 터진다.

In a fight between whales, the shrimp’s back gets broken.

There is an old proverb which describes Korea as a shrimp among whales. Surrounded by larger economic and military powers, Korea has historically needed to align with dominant regional forces to ensure its security and sovereignty. The end of World War II and liberation from Japanese occupation saw the Korean Peninsula and nation split into two different countries. The northern half, with Pyongyang as its capital, came under the Soviet sphere of influence, while South Korea and Seoul were placed under the trusteeship of the United States.

A metropolis that blends Eastern heritage and Western influence, Seoul is a mosaic that evokes both nostalgia and novelty. In fact, the South Koreans have even coined a term for it. Newtro (뉴트로), a portmanteau of the words “new” and “retro,” is an amalgamation of trends from various eras of Korean history. Perhaps this is best experienced with a walk along Cheonggyecheon. A former freeway transformed into a meditative babbling stream, the serene urban park winds through a valley of glittering skyscrapers illuminated by LEDs and reflective windows. Flanking the stream are lively quarters that draw crowds young and old, local and outsider. Some such as Ikseon-dong and Insa-dong are lined with centuries-old hanok buildings. Traditional on the outside, they nevertheless house modern interiors and an array of hip restaurants, cafés, and bars. Others neighborhoods like Myeong-dong are a shopper’s paradise, with countless international and Korean brands and products all competing for attention, from cosmetics to clothing to the latest tech and gadgets.

Come nightfall, the streets burst with color. They whet Seoul in waves of ember-soft lanterns and electric lights, beckoning visitors to explore the flavors hidden behind each sliding door or beaded curtain. From the delicate and refreshing taste of cold buckwheat noodles to the bold zest of yuzu citrus, “Seoul food” is diverse and delicious. An unmissable highlight is the famed Korean barbecue, where thinly sliced beef brisket and soft pork belly melt like butter on the tongue. They are accompanied by a myriad of smaller side dishes, each an individual delight to discover. Like the red-blue taegeuk (태극;太極) on the South Korean flag that symbolize opposing yet complemetary forces, Seoul seamlessly blends the familiar with the foreign, balancing nostalgia and novelty in a harmonious Newtro.